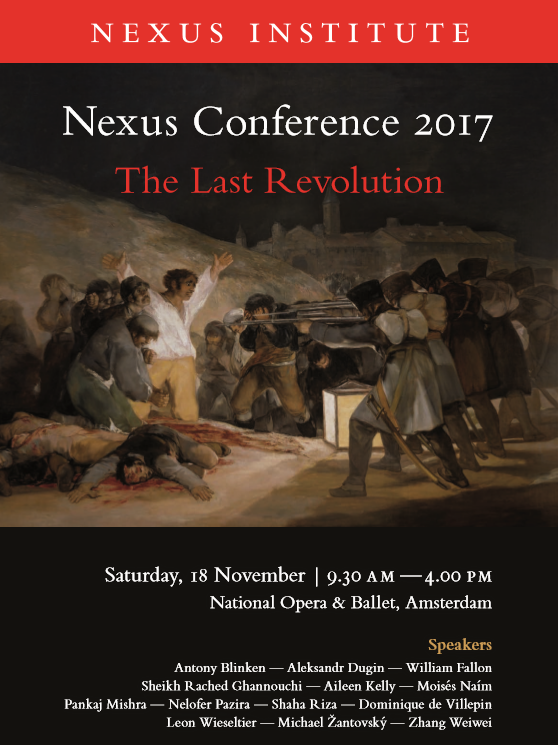

| Nexus Conference 2017 The Last Revolution

Paris, 1850 Yasnaya Polyana, 1869 Prinkipo, 1930 i. the world of power |

| ◄ | THE LAST REVOLUTION: FREEDOM and POWER |

| __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ |

|

In a series of Letters on Toleration, John Locke argued against the exercise of any governmental effort to promote or to restrict particular religious beliefs and practices. His epistemology is directly relevant to this issue: since we cannot know perfectly the truth about all differences of religious opinion, Locke held, there can be no justification for imposing our own beliefs on others. Thus, although he shared his generation's prejudice against "enthusiastic" expressions of religious fervor, Locke officially defended a broad toleration of divergent views.

Locke's political philosophy found its greatest expression in the Two Treatises of Civil Government. The Second Treatise on Government develops Locke's own detailed account of the origin, aims, and structure of any civil government. Adopting a general method similar to that of Hobbes, Locke imagined an original state of nature in which individuals rely upon their own strength, then described our escape from this primitive state by entering into a social contract under which the state provides protective services to its citizens. Unlike Hobbes, Locke regarded this contract as revokable. Any civil government depends on the consent of those who are governed, which may be withdrawn at any time. |

Since standing laws continue in force long after they have been established, Locke pointed out that the legislative body responsible for deciding what the laws should be need only meet occasionally, but the executive branch of government, responsible for ensuring that the laws are actually obeyed, must be continuous in its operation within the society. In similar fashion, he supposed that the federative power responsible for representing this particular commonwealth in the world at large, needs a lengthy tenure. Locke's presumption is that the legislative function of government will be vested in a representative assembly, which naturally retains the supreme power over the commonwealth as a whole: whenever it assembles, the majority of its members speak jointly for everyone in the society. The executive and federative functions, then, are performed by other persons (magistrates and ministers) whose power to enforce and negotiate is wholly derived from the legislative. But since the legislature is not perpetually in session, occasions will sometimes arise for which the standing laws have made no direct provision, and then the executive will have to exercize its prerogative to deal with the situation immediately, relying upon its own counsel in the absence of legislative direction. It is the potential abuse of this prerogative, Locke supposed, that most often threatens the stability and order of a commonwealth.

Revolution Whether any specific use of executive prerogative amounts to an abuse of power, is a question that transcends the social contract itself, and can only be judged by a higher appeal, to the divinely ordained law of nature. Remember that according to Locke all legitimate political power derives solely from the consent of the governed to entrust their "lives, liberties, and possessions" to the oversight of the community as a whole, as expressed in the majority of its legislative body. The commonwealth as a whole, then, is dissolved (and a new one formed) whenever there is a fundamental change in the membership of the legislature. The most likely cause of such a revolution, Locke supposed, would be abuse of power by the government itself: when the society unduly interferes with the property interests of the citizens, they are bound to protect themselves by withdrawing their consent. When great mistakes are made in the governance of a commonwealth, only rebellion holds any promise of the restoration of fundamental rights. Who is to be the judge of whether or not this has actually occurred? Only the people can decide, Locke maintained, since the very existence of the civil order depends upon their consent. On Locke's view, then, the possibility of revolution is a permanent feature of any properly-formed civil society. This provided a post facto defense of the Glorious Revolution in England and was a significant element in attempts to justify later popular revolts in America and France.

|

|

Revolutions continued to occur, and questions about the destiny of humankind and society remain unanswered. Why do revolutions happen? What are the powers that liberate, and what are the powers that oppress? What can we learn from the fact that the French Revolution ended in terror and the Russian Revolution degenerated into totalitarianism, while the American Revolution was successful? |

Will the last revolution be for

freedom and human dignity? |

On Saturday 18 November, the Nexus Institute brought together writers, thinkers, diplomats, politicians and activists from around the world who addressed these questions and looked for answers, ideas and arguments. Which movements will bring freedom in the twenty-first century? Who will oppose power and rise against it? Where will they find strength and inspiration? And what will be the true last revolution? |

|

|

ii. the world of freedom

The brilliant Italian humanist Giovanni Pico della Mirandola is only 24 when, in 1487, he publishes his ode to freedom, De hominis dignitate (‘Oration on the Dignity of Man’), in which he puts these immortal words into the mouth of the Deity: We have given you, Oh Adam, no visage proper to yourself, nor any endowment properly your own, in order that whatever place, whatever form, whatever gifts you may, with premeditation, select, these same you may have and possess through your own judgment and decision. The nature of all other creatures is defined and restricted within laws which We have laid down; you, by contrast, impeded by no such restrictions, may, by your own free will, to whose custody We have assigned you, trace for yourself the lineaments of your own nature. I have placed you at the very centre of the world, so that from that vantage point you may with greater ease glance round about you on all that the world contains. We have made you a creature neither of heaven nor of earth, neither mortal nor immortal, in order that you may, as the free and proud shaper of your own being, fashion yourself in the form you may prefer. It will be in your power to descend to the lower, brutish forms of life; you will be able, through your own decision, to rise again to the superior orders whose life is divine. No matter how elegantly freedom as the essence of mankind has been worded here, the Deity forgets one crucial fact, a fact recorded in His own story of the Creation: the freedom of man begins with rebellion! Only by refusing to obey and by eating from the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil does humanity attain the freedom with which its history begins. Our freedom is always the result of a choice to be free; to orient your thinking against the established order and to be aware that you are responsible for the choice between good and evil. And so the predicament of human existence began. To his great disappointment, Alexander Herzen realized that the revolutions of 1848 and 1849 failed because the masses did not really want to be free. But what is needed to transform the masses into individuals of a united humanity, which cherishes freedom and human dignity? Would that not truly be the last revolution? Rob Riemen Founder and president of the Nexus Institute |

|

‘The Last Revolution’ is a reference to Trotsky’s belief that the Russian Revolution, a hundred years ago by this point, would be the last. For the afternoon debate on the subject ‘the world of freedom’, Aleksandr Dugin and Antony Blinken sat together at a round table, along with other speakers. Dugin, famous as Putin’s philosopher and whisperer, said the following:

Russia has a civilization of its own, which you could call Eurasian. Among us the people, the collective identity with its own history, traditional values and religion, is paramount. God, church and soul determine our human dignity and we detest Western individualism and materialism, the spiritual emptiness that is filled with technology and science. We practise the conservative revolution to guard our own identity, and our greatest enemies are liberalism and globalism. To defend our civilization, Greater Russia must be restored and as a first step towards that we will incorporate the Ukraine once more. The Ukraine is not a country in its own right, it has no culture of its own, Kiev has always been part of Russia. With China and Islam we resist the unipolar world with the global West as its centre and with the United States as its core. This kind of unipolarity has geopolitical and ideological characteristics. Geopolitically, it is the strategic dominance of the Earth by the North American hyperpower and the effort of Washington to organize the balance of forces on the planet in such a manner as to be able to rule the whole world in accordance with its own national, imperialistic interests. It is bad because it deprives other states and nations of their real sovereignty. When there is only one power which decides who is right and who is wrong, and who should be punished and who not, we have a form of global dictatorship. This is not acceptable. The American Empire should be destroyed. There will be war, but our war will be a civilizing mission, just as the European crusades in the Middle Ages. Antony Blinken responded as follows. President Roosevelt provided the American people with a rationale for abandoning isolationism. He argued that our own democracy and the freedoms it guaranteed were at risk: ‘The future and safety of our country and of our democracy are overwhelmingly involved in events far beyond our borders.’ And he looked to a world founded on four essential human freedoms – of speech and religion, and from want and fear – that could only be guaranteed by an engaged America. President Roosevelt laid the foundation for an open, connected America in an open, connected world. Now, the failure to convince of its benefits and address its downsides – and the fears and frustrations of those left out or left behind – risks a fatal crisis of legitimacy for the world that America built. As we build new economic ties – through trade, automation, digitization – how do we ensure that creative disruption does not become destruction of people’s livelihoods and sense of self? As we form new cultural connections – through migration and the adoption of universal norms – how do we preserve traditional values and identities? As we bridge physical borders – accelerating even more the free movement of people, products, ideas and information – how do we simultaneously secure them and our sense of personal safety? As we increase cooperation and coordination among nations – through alliances and international institutions and shared rules – how do we hold onto a sense of national sovereignty? At the heart of these challenges is one of the most powerful human yearnings: for dignity. It informs who we are as individuals, what we are as a nation and where we go as a community of nations. It is an article of faith among democrats that free societies best promote and defend human dignity. |

| Speakers:

Bernard-Henry Lévy | Antony Blinken | Aleksandr Dugin | William Fallon | Sjeik Rached Ghannouchi | Aileen Kelly | Ivan Krastev | Moisés Naím | Nelofer Pazira | Leon Wieseltier | Michael Žantovský | Zhang Weiwei |

Sjeik Rached Ghannouchi, one of the main opponents of the autocratic Tunisian president Kais Saied, has been arrested april 2023 at his home in Tunis. Ghannouchi's party was the largest when Saied dissolved parliament in July 2021. The former parliament speaker is said to have said that a civil war is imminent if political Islam is eradicated. He has already appeared in court in several cases. |